STEELMAKING DEVELOPMENTS: From flame to electricity

In the mid-20th century, steelmaking advanced on many fronts. Basic oxygen steelmaking and electric arc furnaces transformed the main production processes, making them faster and more energy efficient. They even allowed manufacturers to reuse scrap as input material.

Along with introducing new primary techniques, steelmakers also improved on traditional techniques of casting and rolling to create sheets, shapes, and steel to precise customer requirements. Some of these developments came from Europe, the USA, and Russia. But new steelmakers, especially in Japan and Korea, quickly developed their own innovations that in turn inspired steelmakers worldwide.

What exactly were these new techniques? The first – basic oxygen steelmaking – is essentially a refined version of the Bessemer converter, which uses oxygen rather than air to drive off excess carbon from pig iron to produce steel. The process was invented by a Swiss scientist named Robert Durrer in 1948, and was then further developed by Austrian company VÖEST AG (today voestalpine AG). It is also known as the Linz-Donawitz (LD) process, after the Austrian towns in which it was first commercialized.

Most importantly, the process is fast. Modern basic oxygen furnaces (BOFs) can convert an iron charge of up to 350 tonnes into steel in less than 40 minutes – compare this with the 10–12 hours needed to complete a ‘heat’ in an open-hearth furnace.

Making the most of scrap

Seeing the benefits of speed and reduced energy consumption, manufacturers soon began to replace open-hearth furnaces with BOFs. But in the 1960s, scrap from vehicles, household appliances, and industrial waste became a significant, and cheap, resource. The question was, how to reuse it? In a BOF, up to 25% of the charge can be scrap steel.

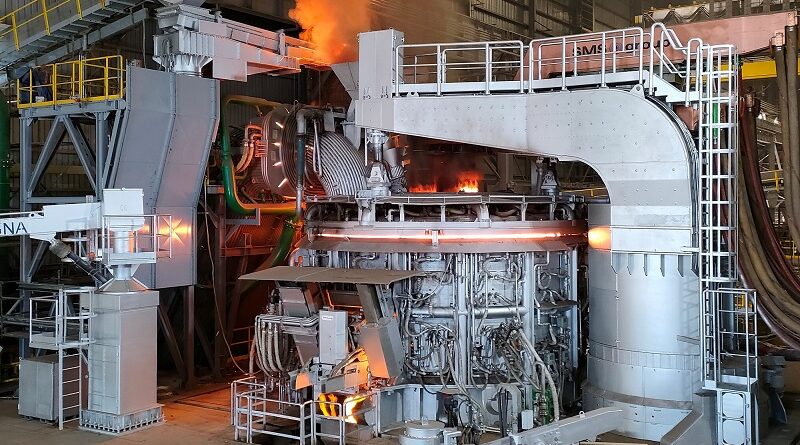

So, innovative steelmakers turned to an old technique and brought it up to date. Electric arc furnaces (EAFs) had first appeared at the end of the 19th century. However, until the 1960s, they were primarily used for specialty steels and alloys.

Now, with abundant scrap, EAFs were suited for larger-scale production. Unlike a BOF, an EAF does not need hot metal – it can be fed with cold or preheated scrap steel or pig iron. The furnace is charged with material and electrodes are lowered into it, striking an arc and thereby generating high enough temperatures to melt the scrap. As with a BOF, the process is quick, typically taking less than two hours. Moreover, EAF plants are relatively cheap to build, which was an important advantage for American and European industries still recovering from a world war.