Africa to become the home of green metals

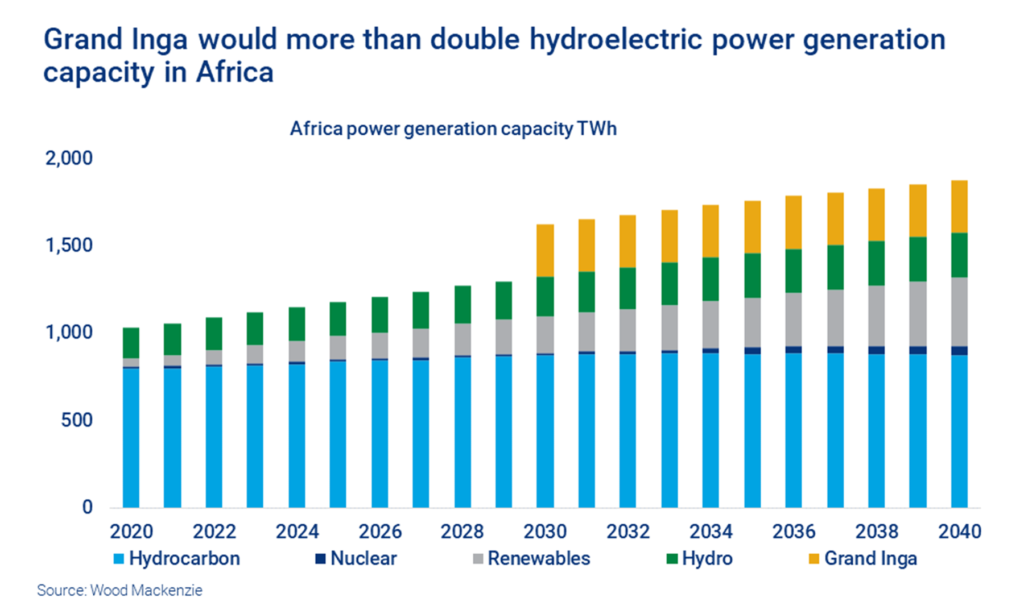

The potentially truly transformational 40 GW Grand Inga and 4.5-12 GW Inga III projects in the DRC come to fruition, they dwarf the vast Three Gorges Dam hydro scheme in China, which has an installed capacity of ‘only’ 12GW, says Wood Mackenzie.

The various Inga hydropower projects have been a dream of development planners for decades. Yet their sheer scale, coupled with the complex politics involved, means their progression and ultimate delivery involve not only far-sighted vision but heroic persistence. And while there is an obvious pun implied by using Franklin’s quote, it is no less true that energy will be required in abundance if the project is to succeed.

A HYDROPOWER PROJECT OF HUGE SCALE

The scale of Inga is immense – both in terms of generating capacity and cost. The Grand Inga alone would more than double Africa’s hydropower generation capacity. Capital costs for the various Inga schemes are equally eye-watering, ranging up to US$100 billion for Inga III and Grand Inga combined.

Will it go ahead? The current status, as we understand it, is that in June 2020 the DRC government presented the project proposal to African regional heads of state, with the aim of establishing the scale of potential demand. So far, South Africa has indicated a willingness to buy 2.5 GW, with Nigeria indicating interest in procuring 3 GW. A further 1.3 GW is targeting the Katanga mining area in the DRC.

WILL THE INGA VISION BECOME REALITY?

While fully exploiting the potential of the Inga Falls has long been a dream of ambitious development planners, events have recently taken a turn towards reality. In June 2021 it was announced that Australian Fortescue Metals Group mining magnate Andrew ‘Twiggy’ Forrest had been granted, subject to final discussions, exclusive rights to develop the Grand Inga project.

So, what’s different now, compared to previous attempts to get the Grand Inga project off the ground? Firstly, the world has changed in the wake of the pandemic. We are now inexorably locked on a lower carbon trajectory and there is a desire to build back better with a more equal distribution of wealth.

Secondly, Andrew Forrest has a vision of a hydrogen future and there are few, if any, undeveloped green energy sources of the scale of Grand Inga. To match action to the rhetoric the Fortescue Metals Group announced the establishment of Fortescue Future Industries, which has been dubbed its ‘green arm’.

Press reports have indicated that the Inga development would include the construction of port infrastructure with green hydrogen and green ammonia production facilities.

A HYDROPOWER-FUELED PARADIGM SHIFT IN AFRICA

While US$100 billion is an enormous amount of money, given Inga’s potential impact — and in the context of an estimated US$50 trillion total bill for the energy transition — it arguably represents good value. However, there is no doubt that politics will play a huge part in how that value is distributed in terms of supplying the resultant green electrons across the continent.

Notwithstanding the broader cross-border political wrangling that will no doubt ensue, there is also the important issue of how best to harness Inga’s energy to capture value. Africa has long made clear its ambitions to reduce the export of raw ore and add value to its under-developed natural resource base.

Various governments have hatched plans over the years to process ore into metal, thereby creating jobs and keeping more of the wealth within their borders. Many of these plans have failed due to a lack of economic energy supply.

Combine the global drive to reduce carbon emissions with the opportunity to supply low-carbon electrons on a scale that can meet continental needs and in my view you create the catalyst for a new paradigm.

WILL POLITICS ACCELERATE OR HINDER THE GREEN ELECTRONS?

Grand plans to convert hydropower into exportable hydrogen or ammonia-based energy will benefit the region while also assisting the carbon reduction strategies of emitters in the steel value chain, amongst others.

That may be enough for the incumbent DRC government, but may not meet future political objectives in terms of value share, job creation, decarbonisation and extracting value from underdeveloped natural resources. These four issues are Africa-wide and resolution would require the transmission of Grand Inga’s hydropower across the continent – which is where politics will, once again, rear its head.

Weaning Africa off hydrocarbon-based power would of course be a positive outcome. There may, however, be an opportunity for something even more visionary and transformative. The immense supply of green energy Inga would generate could be used to enable full value chain conversion of West Africa’s vast iron ore and bauxite deposits.

Iron ore could be converted into ‘green’ steel using a process such as the Hybrit method under development by SSAB, LKAB and Vattenfall in Sweden. This requires an abundance of green hydrogen and green electricity to produce sponge iron — enter stage left Andrew Forrest and his DRC-generated green hydrogen and hydropower.

On the aluminium front, it’s essentially the same story. Access underdeveloped bauxite resources, then convert to alumina using green power — electrically-heated steam and hydrogen calcination (the latter is under early-stage investigation by Rio Tinto in Australia). Conversion into green aluminium would be achieved using inert anode technology.

Aside from the reduction in direct emissions, a far simpler and shorter supply chain would lower transportation emissions. There would also be the added benefits of high-value job creation and significant tax receipts. Overall, such a strategy could provide an accelerated development path for countries that can, in some instances, feel that they have been used primarily as a source of ore.