GREEN SMELTING: copper, zinc and lead making under microscope

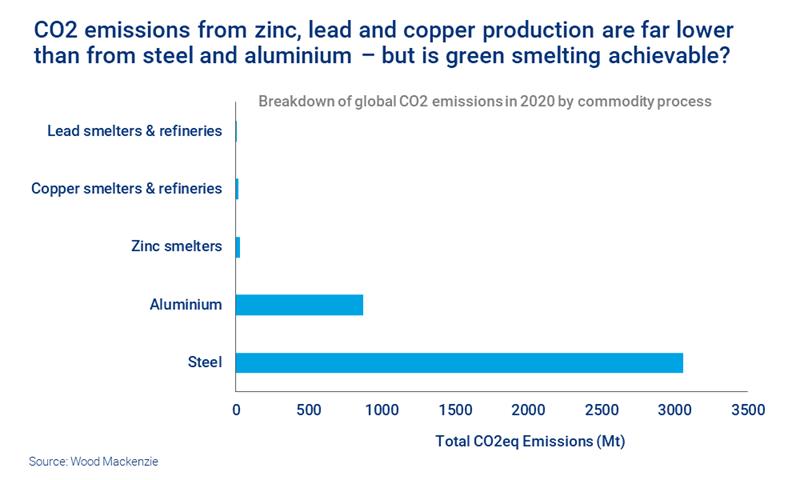

With 2021 shaping up to be the year the world got serious about decarbonisation, every sector can expect to come under the climate change microscope, says Wood Mackenzie. The vast carbon emissions from steel and aluminium production often overshadow the environmental impact of zinc, lead and copper smelting.

But the energy-intensive process of producing these metals is far from squeaky clean. So, is green smelting achievable, and what are the obstacles to making it happen?

EMISSIONS FROM COPPER, ZINC AND LEAD SMELTING

Wood Mackenzie assessed global emissions from the smelting of lead, zinc and copper. As you can see from the chart below, when compared to emissions from aluminium and especially steel , the carbon emitted may, at a glance, appear insignificant.

According the Wood Mackenzie estimates, smelting of zinc, copper and lead still produced a combined 53 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2020. It forecasts that from 2020 to 2040, zinc production will increase by over 30%, lead by over 40% and copper by more than 45%. If there is no change in the core technologies or power sources used to produce these metals, a total of 1,008 MtCO2e will be emitted over the next 20 years.

In the face of increased scrutiny, continuing to play by current environmental rules is not an option for smelters. A proactive approach to decarbonising production is needed.

WHAT IS GREEN SMELTING?

Green smelting means using improved technology and processes to reduce:

- sulphur and nitrogen oxide (SOx and NOx) emissions, which can cause acid rain

- the release of metals directly to air and water as waste

- CO2 emissions created through process operations or electricity consumption.

The first step in base smelting is the removal of sulphur from the raw materials in the form of sulphur dioxide, which can be captured to make sulphuric acid. The development of acid plant technology means SOx emissions from most smelters today are in the order of parts per million. The industry can go further by adopting scrubber technology, but this is only likely to happen if emission limits are tightened. The same logic applies to NOx emissions.

In the case of CO2 and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, tackling direct (Scope 1) and indirect (Scope 2) emissions will be key.

Scope 1 emissions come typically from using coal, coke, natural gas or oil in the production process. For copper and lead smelters, green hydrogen could theoretically be used instead. For zinc smelting, the issue is with residue treatment where there are two process options.

The first employs a pyrometallurgical technique which involves coal or coke, while the second uses hydrometallurgical technology. The latter might seem environmentally preferable, but it creates a hazardous residue. Research is ongoing to extract further metals and make such waste more benign.

Scope 2 emissions are those associated with the source of the grid power used in the production process. For zinc smelters, 56% of GHG emissions are thus attributable to over 3,000 kilowatt hours per tonne (kWh/t) of metal being used in the electrowinning tankhouse.

By comparison, the electrorefining of lead and copper is much less energy intensive, requiring 3-400 kWh/t metal. For copper smelters, 51% of the GHG emissions come from the power used (mainly to make oxygen). Meanwhile, for copper refineries it is a huge 88%.

With a large part of the sector’s environmental impact coming from electricity generation, the use of entirely renewable sources of power could significantly reduce overall emissions.

GREEN SMELTING: CAN IT BE DONE?

Renewable energy was already used to smelt 40% of zinc and 32% of lead produced in 2020 – and that can be scaled up. But can it hit 100%? Based on the Wood Mackenzie review of the power mix of the top 10 copper, zinc and lead producing countries, it’s unlikely. Smelters in these countries cannot get 100% of their power need via the grid from renewable sources, now or even in the future.

As things stand, by 2040 over 90% of zinc production will still come from smelters that draw only 30-60% of their grid power from renewable sources. For copper and lead the outlook is even worse.

One solution is to build new and replacement smelting capacity close to existing or planned sources of renewable power. Another is for smelters to build dedicated solar or wind installations to serve their facilities, either on their own or in partnership with renewable energy providers.