STEELMAKING: 20th century global expansion, 1900-1970s

By the dawn of the 20th century, steelmaking was a major industry and science was increasingly unlocking the mysteries of steel. A British ‘gentleman scientist’ named Henry Clifton Sorby created a sensation by putting metal samples under a microscope. His pioneering work revealed steel’s secret – it gained its strength from the small, precise quantities of carbon locked within the iron crystals.

This was also an age of great industrialists. In the US, J.P. Morgan bought out Andrew Carnegie’s steel business to form the United States Steel Corporation in 1901, which founded the city of Gary, Indiana in 1906 as the home for its new plant – Gary was named after Elbert Henry Gary, founding chairman of US Steel. Morgan had learned from Carnegie that integrating all parts of the manufacturing process into one single organization could lead to efficiencies in process and scale.

Manufacturing processes evolved too. The open-hearth process gradually replaced the Bessemer process as the primary method for steel production. Although slower, this drawback was also its advantage – plant chemists had time to analyze and control the quality of the metal during the refining process, resulting in stronger grades of steel.

With greater understanding of the properties of steel, steel alloys became more widespread. In 1908, the Germania, a 366-tonne yacht built by the Friedrich Krupp Germania shipyard had a hull made of chrome-nickel steel. And in 1912, two of Krupp’s German engineers, Benno Strauss and Eduard Maurer, patented stainless steel, the invention of which is in fact usually credited to Harry Brearley (1871-1948), a Sheffield-born English chemist who, during his work for one of the city’s laboratories, began to research new steels that could better resist the erosion caused by high temperatures, and examine the addition of chromium, which eventually resulted in the creation of what is probably the best-known alloy of all.

The 20th century’s two world wars had huge consequences for steelmaking. Like other heavy industries, steelmaking was nationalized in many countries due to demands for military equipment. Steel was required for the railways and ships that carried troops and supplies.

Military vehicles and particularly the tank also relied heavily on steel. From their invention until the end of the Second World War, tanks were protected by steel plates with a uniform structure and composition known as rolled homogenous armor (RHA). This type of armor was so universal that it became the standard for determining the effectiveness of anti-tank weapons.

After the austerity of the Second World War, trade and industry revived. Steel that once went to make tanks and warships now met consumer demand for automobiles and home appliances. Populations boomed and so did construction. As more people moved into cities, buildings became larger and taller, and huge quantities of steel were required for girders and reinforced concrete.

Growing prosperity and technological innovation transformed everyday life. By the 1960s, mass-produced electrical appliances became increasingly accessible to millions of consumers. These included refrigerators, freezers, washing machines and tumble dryers, etc. And the iconic shipping container – designed in 1955 and made of steel – provided a strong, safe way to transport all these goods by ship, road and rail.

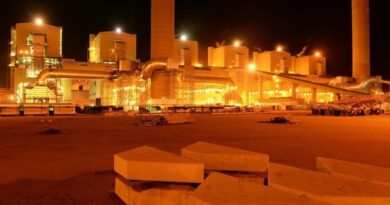

Obviously, the automobile quickly became a hugely popular mass-consumption item, transforming the landscape and leading to the development of the oil and gas industry, a process that involved all types of steel product.