Will green steel compete with conventional steel on cost?

Proactive initiatives and abundant renewables could see Sweden take the lead in the race to decarbonise steel.

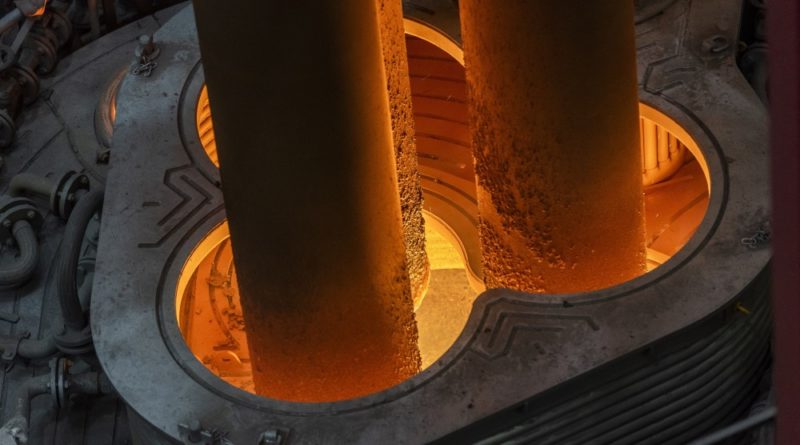

The global steel industry is responsible for between 7% and 9% of annual carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. That alone is enough for the sector to embark on a decarbonisation drive. Add to the mix the primary role that steel will play in the global energy transition and the need for greener solutions only intensifies.

Put simply, renewables need fossil-free steel to achieve carbon neutrality. Right now, for instance, steel contributes 65% and 94% of raw material emissions of onshore and offshore wind turbines, respectively. At the same time, renewables are the key enabler for the European steel industry to reach its emissions reduction target of 80-95% by 2050.

The race to decarbonise steel is on – and Sweden looks like a likely contender to take the lead. About 80% of the 28 ‘green’ steel ventures currently active across the continent aim to utilise hydrogen produced from renewable energy as an alternative fuel for steel production, replacing coal-intensive coking. Swedish initiatives stand out for their ambition to decarbonise the value chain from iron ore mining to crude steel.

When can green steel compete with conventional steel on cost? Fairly soon. Latest research shows a strong case for green steel to reach cost parity with conventional steel this decade, under the right conditions.

The nature and expanse of technological innovation required for green steel ventures to succeed is not unique. The decarbonisation of heavy industry has several moving parts that must prove their reliability individually and as a synchronised sum. However, there are several reasons to argue that green steel has a brighter future than conventional steel.

First, various steel companies have produced fossil-free steel already. The challenge of deploying these solutions at an industrial scale is sizable, but we expect it to lessen in the 2030s through an iterative process.

Second, the policy and regulatory frameworks will become conducive in the coming years, given the government’s pledge to carbon neutrality. Nonetheless, local opposition towards new renewable energy plants will test the resolve of developers for years to come.

Finally, public funds are available to lower the financial risk of green steel developments. Sweden’s HYBRIT is among seven projects selected by the EU for a Euro 1.1 billion investment. More importantly, the superior economics of green steel will stimulate the flow of low-cost capital. That in turn will aid developers to expand production and maximise economies of scale through the 2030s and 2040s.